Understanding Your BMI Result: What It Means for Your Health

Estimated reading time: about 5 minutes

This information is for general education purposes and does not replace medical assessment, diagnosis or personalised care from a healthcare professional.

Body Mass Index (BMI) is a widely used screening tool that helps estimate weight-related health risk at a population level. It is calculated using height and weight, and it is often used as a starting point for understanding whether a person may be underweight, within a healthy weight range, living with overweight, or living with obesity.

However, while BMI can support early identification of risk, it does not provide a complete picture of health. Contemporary obesity guidelines emphasise that obesity is a complex, chronic condition that requires comprehensive clinical assessment, rather than reliance on BMI alone.

At BeyondBMI, we use BMI as part of a broader evidence-based approach to support adults in Ireland seeking structured weight management care.

This article refers to BMI interpretation in adults. Different assessment methods are used in children and adolescents.

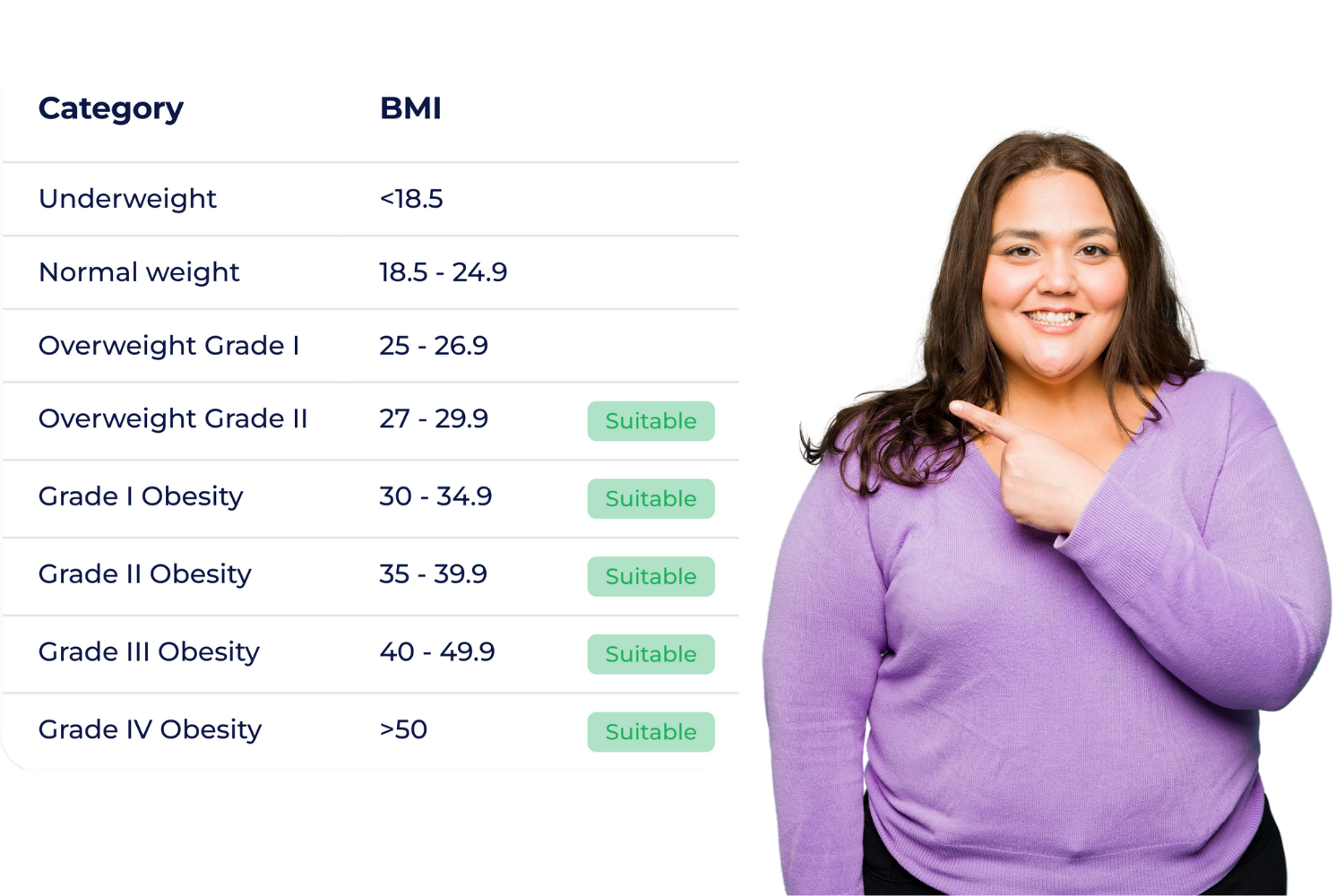

The image is a model

What Is BMI?

BMI is calculated by dividing weight (kg) by height squared (m²). This produces a numerical result that is commonly used to classify weight categories in adults.

Adult BMI Categories (General Thresholds)

BMI is typically interpreted using the following adult categories:

Underweight: BMI below 18.5

Healthy weight range: BMI 18.5 to 24.9

Overweight: BMI 25 to 29.9

Obesity (Class I): BMI 30 to 34.9

Obesity (Class II): BMI 35 to 39.9

Obesity (Class III): BMI 40 or above

In Ireland, the HSE also highlights that BMI and waist circumference may be assessed together, because abdominal fat distribution can influence metabolic risk and long-term outcomes.

What Your BMI Result May Indicate

BMI categories can be useful for identifying when an individual may benefit from preventive action or structured clinical support. However, the recommended approach differs depending on the BMI range and the person’s broader health profile, including whether weight-related complications are already present.

1) If Your BMI Is Below 18.5 (Underweight)

A low BMI can sometimes suggest inadequate nutritional intake, underlying illness, or other health concerns that merit medical evaluation. A clinician can support appropriate assessment and follow-up where needed.

2) If Your BMI Is 18.5–24.9 (Healthy Weight Range)

This range is generally associated with lower risk of weight-related disease compared to higher BMI categories. Maintaining consistent eating patterns, regular movement, and good sleep quality can support long-term health.

BMI can provide useful population-led information, but it cannot determine an individual's health. People in any BMI category may experience medical conditions, which is why broader medical assessment is always important.

3) If Your BMI Is 25–29.9 (Overweight)

In this range, risk may increase over time - particularly when combined with additional clinical risk factors (such as hypertension, dyslipidaemia, or impaired glucose regulation). Irish and international clinical pathways often recommend early lifestyle-based interventions and monitoring, with escalation of care based on health status and complications.

4) If Your BMI Is 30 or Higher (Obesity)

A BMI of 30 or above is commonly associated with increased risk of obesity-related complications, and many guidelines recommend structured medical support for assessment and management.

Modern clinical guidance recognises obesity as a chronic disease that is manageable but typically requires a long-term approach.

Why BMI Matters: Understanding Health Risk

BMI is not used to diagnose a specific disease, but it can help estimate risk. Evidence from systematic reviews and large prospective studies shows consistent associations between higher BMI and increased risk of multiple health conditions, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, and some cancers.

Several clinical guidelines also highlight that obesity is frequently associated with comorbidities, and effective obesity care includes assessment for complications as part of treatment planning.

Examples of obesity-associated conditions frequently assessed in clinical practice include:

Type 2 diabetes

Cardiovascular disease risk

Hypertension

Sleep apnoea and breathing issues

Osteoarthritis and joint strain

Because risk increases as BMI rises, earlier evidence-based intervention may support better long-term outcomes.

The Limitations of BMI: Why One Number Is Not the Whole Story

Although BMI is widely used, clinical obesity guidelines caution that BMI does not directly measure body fat percentage, does not capture fat distribution, and may misclassify risk in some individuals (for example, those with higher muscle mass or different body composition).

That is why clinical pathways frequently recommend combining BMI with additional measures such as:

Waist Circumference

The HSE highlights waist circumference as a useful measure in clinical assessment, particularly where abdominal fat distribution increases cardiometabolic risk.

Clinical Evaluation and Complications Screening

International obesity guidelines recommend evaluating weight history, health complications, and functional impact, rather than relying on BMI alone.

BMI and Ethnicity: Interpreting Risk More Accurately

Evidence suggests that individuals from different ethnic backgrounds may have different health risks at the same BMI due to differences in fat distribution and body composition. This has led to proposals for ethnicity-adjusted BMI thresholds in some populations, particularly among Asian groups.

This is clinically relevant because BMI should be interpreted within context, and personalised assessment may be needed for accurate risk evaluation.

What to Do After You Check Your BMI

BMI can be a useful starting point, but the next steps should be guided by your overall health, not the number alone.

If You Are Concerned About Your BMI

In Ireland, the HSE advises that obesity assessment may involve BMI alongside additional clinical measures, including waist circumference. If your BMI suggests elevated risk, or if you have symptoms or existing health conditions, it can be helpful to discuss this with a healthcare professional and consider a broader clinical assessment.

If you would like to continue learning about evidence-based weight management, you can explore additional articles in the BeyondBMI blog.

Conclusion

BMI remains a useful screening tool for understanding weight-related risk, but it should not be viewed as a complete measure of health. Clinical best practice increasingly supports comprehensive obesity assessment, including metabolic health, fat distribution, and functional impact, particularly for individuals living with overweight or obesity.

If your BMI suggests increased risk, structured, evidence-based care can help you take practical next steps in a sustainable way.

Q&A

Is BeyondBMI the treatment I need?

BeyondBMI is a medical treatment designed for people with obesity (BMI ≥ 30) or grade II overweight (BMI ≥ 27) with at least one weight-related health condition (for example: prediabetes/diabetes, hypertension, high cholesterol, PCOS, sleep apnoea, osteoarthritis, etc.). You can calculate your BMI and find out if you meet the criteria to access this programme, which combines pharmacological treatment(*) and comprehensive support.

* Medications are not included in the membership programme. BeyondBMI is a method in which one of our registered doctors decides whether or not medication is necessary and, if so, which one is most suitable for your treatment. Medication decisions are only made following full medical assessment.

To understand how the programme works in practice, you can read more on our programme.

Why is BeyondBMI a unique solution?

It’s a comprehensive medical method, not an isolated treatment. We take care of your health from day one to achieve real and sustainable change.

It’s designed by a dedicated team of specialists (Doctors, Dieticians, Health Coaches and Psychologists) all trained in Obesity Management in Ireland.

It offers continuous support, without friction, travel, or waiting - an accessible and 100% digital method, from people to people.

-

Bhaskaran, K., Dos-Santos-Silva, I., Leon, D.A., Douglas, I.J. and Smeeth, L. (2018). Association of BMI with overall and cause-specific mortality: a population-based cohort study of 3.6 million adults in the UK. The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology, [online] 6(12), pp. 944–953. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1016/s2213-8587(18)30288-2

Deurenberg-Yap, M., Schmidt, G., van Staveren, W. and Deurenberg, P. (2000). The paradox of low body mass index and high body fat percentage among Chinese, Malays and Indians in Singapore. International Journal of Obesity, 24(8), pp.1011–1017. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/sj.ijo.0801353

Garvey, W.T., Mechanick, J.I., Brett, E.M., Garber, A.J., Hurley, D.L., Jastreboff, A.M., Nadolsky, K., Pessah-Pollack, R. and Plodkowski, R. (2016). American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology comprehensive clinical practice guidelines for medical care of patients with obesity. Endocrine Practice, 22(Suppl 3), pp. 1–203. doi:https://doi.org/10.4158/ep161365.gl.

Guh, D.P., Zhang, W., Bansback, N., Amarsi, Z., Birmingham, C.L. and Anis, A.H. (2009). The incidence of co-morbidities related to obesity and overweight: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health, 9(1), p. 88. doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-9-88.

The Nutrition Source. (2022). Body Fat. [online] Available at: https://nutritionsource.hsph.harvard.edu/healthy-weight/measuring-fat/.

HSE.ie. (2025). Obesity Diagnosis. [online] Available at: https://www2.hse.ie/conditions/obesity/diagnosis/.

Health Service Executive (HSE) (2023) Healthy Eating Active Living Implementation Plan 2023–2027. Available at: https://www.hse.ie/eng/about/who/healthwellbeing/our-priority-programmes/heal/the-healthy-eating-active-living-implementation-plan-2023-2027.pdf

HSE/ICGP (2015) Weight Management Treatment Algorithm. Available at: https://www.nrh.ie/wp-content/uploads/2015/11/Weight-Management-Treatment-Algorithm-HSE-ICGP.pdf (Accessed: 16 January 2026).

Hussain, A., Claussen, B., Ramachandran, A. and Williams, R. (2010) ‘Type 2 diabetes and obesity: a review’, Journal of Diabetology, 2, pp. 1–7.

Janssen, I., Katzmarzyk, P.T. and Ross, R. (2004). Waist circumference and not body mass index explains obesity-related health risk. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 79(3), pp.379–384. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/ajcn/79.3.379

Katzmarzyk, P.T., Reeder, B.A., Elliott, S., Joffres, M.R., Pahwa, P., Raine, K.D., Kirkland, S.A. and Paradis, G. (2012). Body Mass Index and Risk of Cardiovascular Disease, Cancer and All-cause Mortality. Canadian Journal of Public Health, 103(2), pp.147–151. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/bf03404221

Landi, F., Calvani, R., Picca, A., Tosato, M., Martone, A.M., Ortolani, E., Sisto, A., D’Angelo, E., Serafini, E., Desideri, G., Fuga, M.T. and Marzetti, E. (2018). Body Mass Index Is Strongly Associated with Hypertension: Results from the Longevity Check-up 7+ Study. Nutrients, [online] 10(12), p.1976. doi:https://doi.org/10.3390/nu10121976

National Library Of Medicine (2015). Obesity Screening: MedlinePlus Lab Test Information. [online] Medlineplus.gov. Available at: https://medlineplus.gov/lab-tests/obesity-screening/

NIH (2022). Heart-Healthy Living - Aim for a Healthy Weight | NHLBI, NIH. [online] www.nhlbi.nih.gov. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/heart-healthy-living/healthy-weight.

Novo Nordisk (2025). Understanding Your BMI Result. [online] Novocare.global. Available at: https://www.novocare.global/global/en/managing-your-weight/understanding-your-bmi-result.html.

Nuttall, F. (2015). Body Mass IndexObesity, BMI, and Health A Critical Review. May/June 2015 - Volume 50 - Issue 3 : Nutrition Today. [online] journals.lww.com. Available at: https://journals.lww.com/nutritiontodayonline/Fulltext/2015/05000/Body_Mass_Index__Obesity.

Canadian Adult Obesity Clinical Practice Guidelines (2020). Assessment of People Living with Obesity. Available at: https://obesitycanada.ca/wp-content/uploads/2025/03/6-Canadian-Adult-Obesity-CPG-Obesity-Assessment.pdf.

Prospective Studies Collaboration (2009). Body-mass index and cause-specific mortality in 900 000 adults: Collaborative analyses of 57 prospective studies. The Lancet, [online] 373(9669), pp.1083–1096. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(09)60318-4.

Romero-Corral, A., Caples, S.M., Lopez-Jimenez, F. and Somers, V.K. (2010). Interactions Between Obesity and Obstructive Sleep Apnea. Chest, [online] 137(3), pp.711–719. doi:https://doi.org/10.1378/chest.09-0360.

Wen, C.P., David Cheng, T.Y., Tsai, S.P., Chan, H.T., Hsu, H.L., Hsu, C.C. and Eriksen, M.P. (2009). Are Asians at greater mortality risks for being overweight than Caucasians? Redefining obesity for Asians. Public Health Nutrition, 12(04), p.497-506. doi:https://doi.org/10.1017/s1368980008002802.

WHO (2004). Appropriate body-mass index for Asian populations and its implications for policy and intervention strategies. The Lancet, [online] 363(9403), pp.157–163. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(03)15268-3.

Yumuk, V., Tsigos, C., Fried, M., Schindler, K., Busetto, L., Micic, D. and Toplak, H. (2015). European Guidelines for Obesity Management in Adults. Obesity Facts, 8(6), pp.402–424. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000442721.

Zheng, H. and Chen, C. (2015). Body mass index and risk of knee osteoarthritis: systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. BMJ Open, [online] 5(12), p.e007568. doi:https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2014-007568.

Heymsfield, S.B., Peterson, C.M., Thomas, D.M., Heo, M. and Schuna, J.M. (2015). Why are there race/ethnic differences in adult body mass index-adiposity relationships? A quantitative critical review. Obesity Reviews, [online] 17(3), pp.262–275. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/obr.12358.